A new article in AI Magazine draws an illuminating comparison between what AI is doing to writing and what photography did to art in the 1840s. It helps to make sense of a question many of us are thinking about more often: does increasing reliance on AI signal the end of writing?

The insights in this piece resonate with me, given the quantum leap in my own use of AI over the past few months.

I’m now making such frequent use of it — integrating it into my research, writing, and editing — that it has me wondering what’s really happening.

As I describe in a piece for the CBA’s National Magazine, I’ve been dipping in and out of Claude, ChatGPT, and Perplexity constantly — to get a quicker lay of the land on new topics, reword sentences, and tighten drafts. But the pace and intensity feel like a transformation as momentous as the shift from typewriter to computer, or from paper-based research to the internet.

To be clear, I’m not using AI to create texts. But using it more often to edit, it sometimes causes me to think about my claim to authorship. At what point does a suggestion — or re-write of a paragraph — mean it’s no longer me?

In “Reclaiming authorship in the age of generative AI: From panic to possibility,” Mohsen Askari argues that we need to abandon the notion that “authorship is defined by the absence of tools” — that using AI contaminates the purity of writing.

He sees AI as part of a continuum of tools from the pen to the typewriter to the reference manager. His central claim is provocative: “[w]hat matters is not whether help was involved, but whether the author stands behind the final work.”

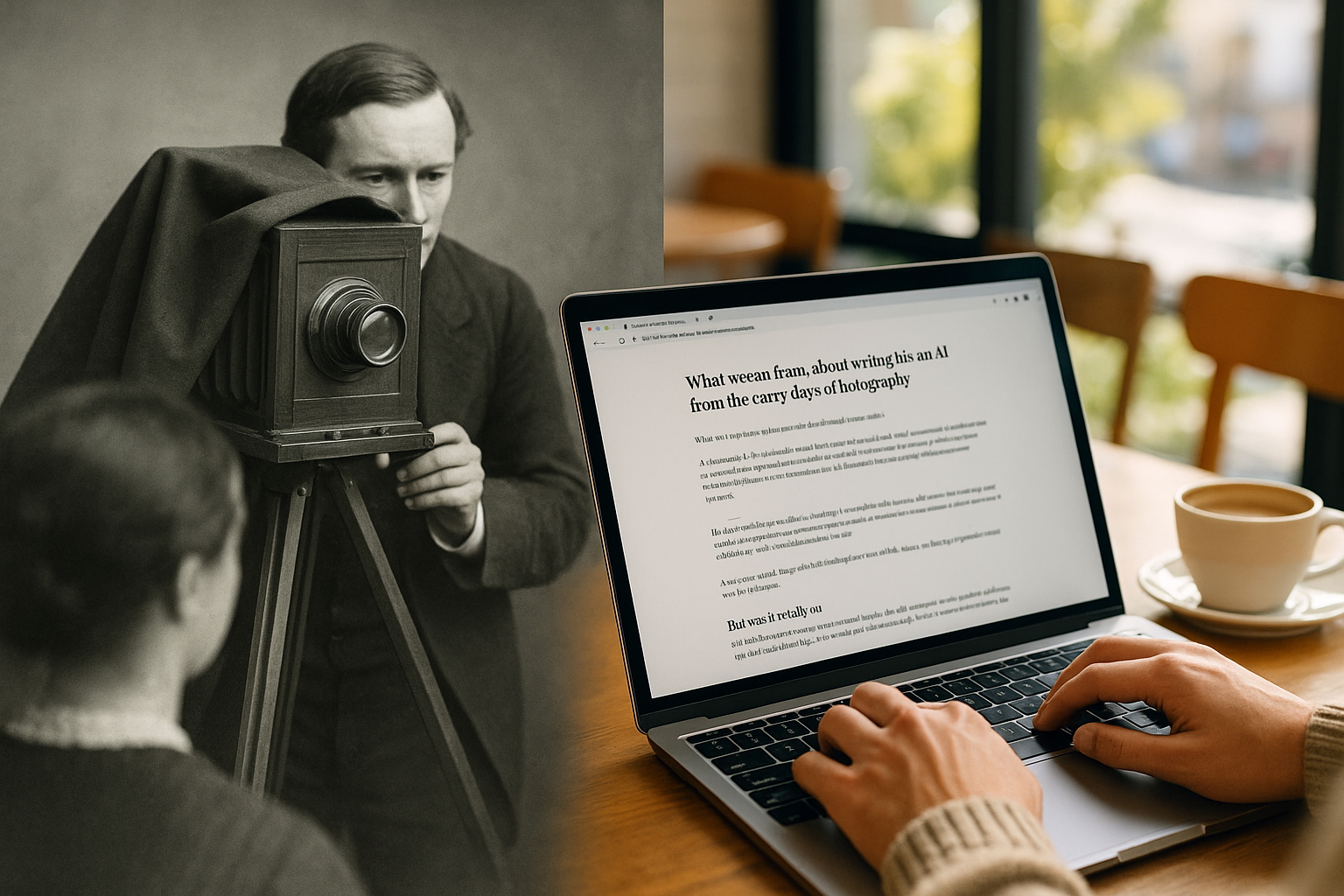

Why AI is like early photography

The sharpest part of his piece is the analogy to photography in France in 1839. Painter Paul Delaroche famously declared: “From today, painting is dead!” The camera’s ability to mechanically capture the world posed an existential threat to painting not unlike our response to AI in writing: “shock, suspicion, and widespread declarations of the end of a creative tradition.”

Early photography was dismissed as craftless. It seemed to require “no imagination, no hand, and no labour.” The prestige artists earned for mastery evaporated. Photography “democratized image-making.”

But painting didn’t die. It ceased to be about reproduction and exploded with creativity through abstraction and experimentation. Meanwhile, photography itself became an art form: “Mastery emerged not from the act of clicking a shutter, but from timing, framing, lighting, and selection. In short: from judgment.”

Askari sees the same happening with AI. Like photography, it produces results quickly and provokes fears of “fraudulence and depersonalization.” Yet using AI well involves more than typing a prompt; it requires “knowing what to ask, how to evaluate, when to refine, and when to reject.”

AI can produce fluent text, he notes, but fluency is “not the same as quality, insight, or originality.” The real work lies in “asking the right questions, rephrasing, discarding early results, and returning with a clearer intent.”

For Askari, writing with AI remains authorship when it involves real “sculpting”: “The user curates meaning. They filter the signal from the noise. Above all they remain accountable for what is kept and what is removed.”

But is it really you?

Askari may be stretching it too far. Surely authorship is more than “augmentation” or “curation.”

But he has a point: authorship can be authentic even if not every sentence is one’s own. In conversation, we often grope toward an idea only for a friend to supply the better phrasing, which we readily adopt. They give us the words; we provided the idea. The proof is that our friend doesn’t just nod but lights up with an “aha.” This is the distinction Askari seems to be after.

For people pressed with time, living with “interrupted attention spans,” or working in “linguistically diverse environments,” AI, he says, isn’t a “crutch or a cheat,” but a “tool that enables a different kind of flow.”

In the academy, the flow he describes sparks anxiety because AI makes suddenly “easier, faster, and more accessible” skills that once took years to develop: “the ability to write well, think clearly, and publish independently.”

We’re still aiming to cultivate these skills rather than handing them off to AI. How do we do this when AI offers to do it all for us?

What about student assignments?

When students hand in work with a strong trace of AI—a paper more polished than we suspect they would have written on their own—Askari urges us to question the reflexive view that AI use entails “the absence of thought.” He suggests we see the tool not as disrupting writing, but as having “supported” it.

The question, he writes, is not “whether AI was used, but whether the author remained present, intentional, and accountable throughout the process.”

This framing helps.

When I recently used AI to revise the opening of a piece, I wondered whether it was still my writing if I adopted the suggestion. Askari’s point is that it’s yours not because you accept AI’s wording, but because what AI is rewording is your idea.

If there’s a visible trace between your draft and AI’s output, then yes, you wrote it. AI only helped.

But what about the term paper I received last spring in one of my courses that seemed written entirely by AI? Askari would say this wasn’t authorship any more than pointing a camera out a window and clicking would be art.

It fails because the student had not “remained present, intentional, and accountable throughout the process.” They simply pointed and clicked. And that’s why it felt wrong.

We might conclude that what matters is not whether AI polished a student’s prose, but whether we can still detect presence and intentionality. Original ideas, analogies, connections.

The line will often be subtle. How much originality or intent is enough? How do we measure it? How do we teach students not to over-rely on AI?

Not easy questions. But Askari’s insights remain useful.